💡 Quick Answer: The Big Dipper is not a constellation. It is an “asterism” (a recognizable star pattern) that forms the tail and hips of the larger constellation Ursa Major (The Great Bear).

Ursa Major (Big Dipper): The Indispensable Northern Icon

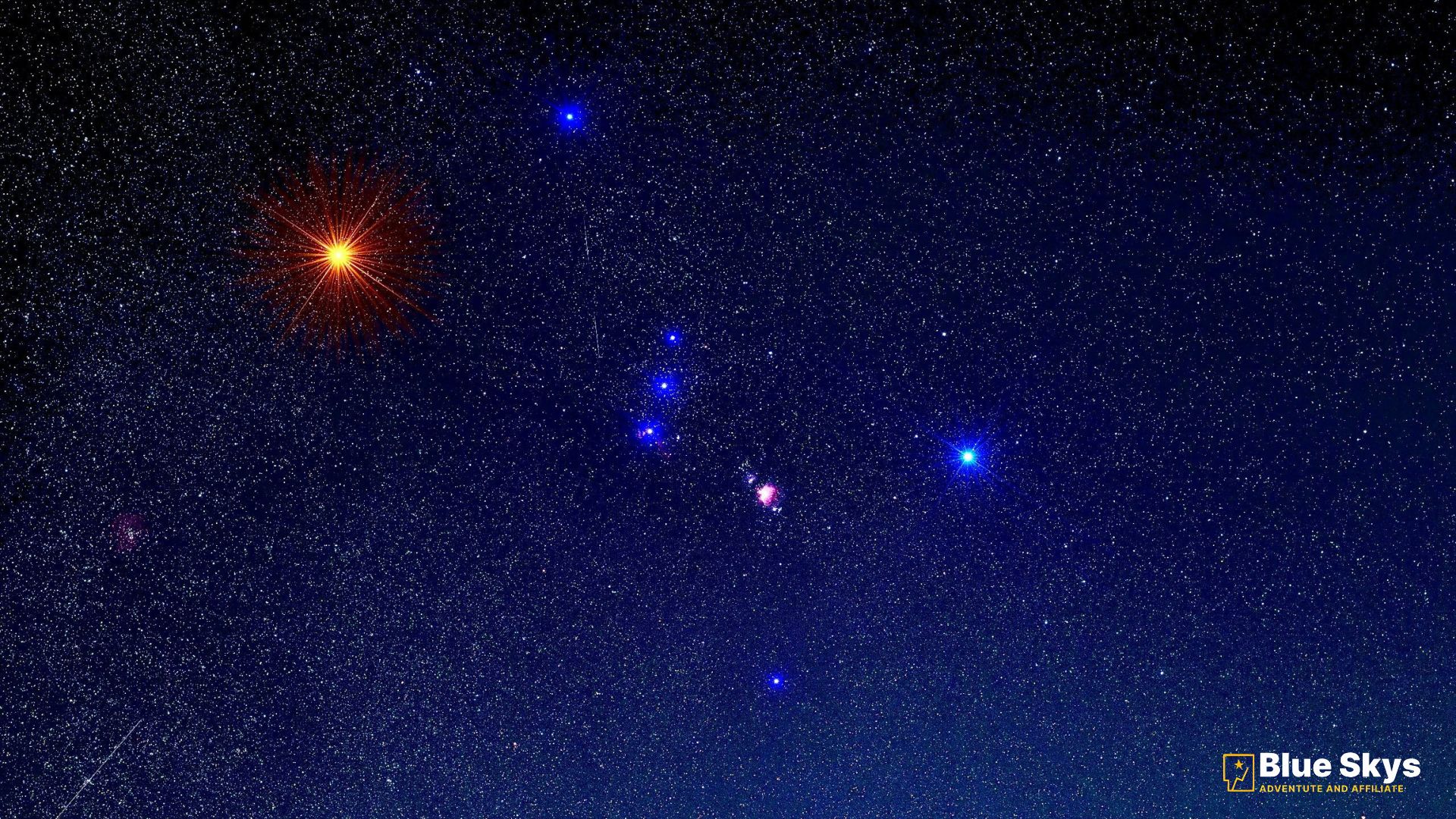

Most people can spot the Big Dipper. It is the most famous pattern in the northern sky. But here is the secret most beginners miss: The Big Dipper is just a small part of the story.

It is actually the tail of a much larger, majestic beast: Ursa Major, the Great Bear. In this guide, we will show you how to find the full Bear, how to use its famous “Pointer Stars” to navigate, and why this single constellation is the key to unlocking the entire night sky.

👀 Can I see the Big Dipper tonight?

- 🇺🇸 USA / 🇬🇧 UK / 🇨🇦 Canada: YES. Visible all night. Look North. It will be low on the horizon in autumn evenings and high overhead in spring.

- 🇦🇺 Australia / 🇳🇿 NZ: NO. The Big Dipper is not visible from most of the Southern Hemisphere (south of 25°S). Look for the Southern Cross instead!

The Ultimate Sky Hack: Finding North with the Big Dipper

Before GPS, sailors used Ursa Major to navigate the open oceans. You can use the same trick tonight to find your way in the dark.

The “Pointer Stars” Method:

- Find the Bowl: Look for the four bright stars that form the “cup” of the Dipper.

- Spot the Edge: Focus on the two outer stars of the bowl, named Dubhe and Merak.

- Draw a Line: Imagine a straight line shooting out from Merak, through Dubhe, and into the sky.

- Find Polaris: Extend that line about 5 times the distance between the two stars. The first bright star you hit is Polaris (The North Star).

Pro Tip: Once you find Polaris, you are facing True North. Polaris also marks the handle of the “Little Dipper” (Ursa Minor).

Constellation vs. Asterism: Defining the Great Bear

To fully understand this celestial giant, we must distinguish between the “Bear” and the “Dipper.”

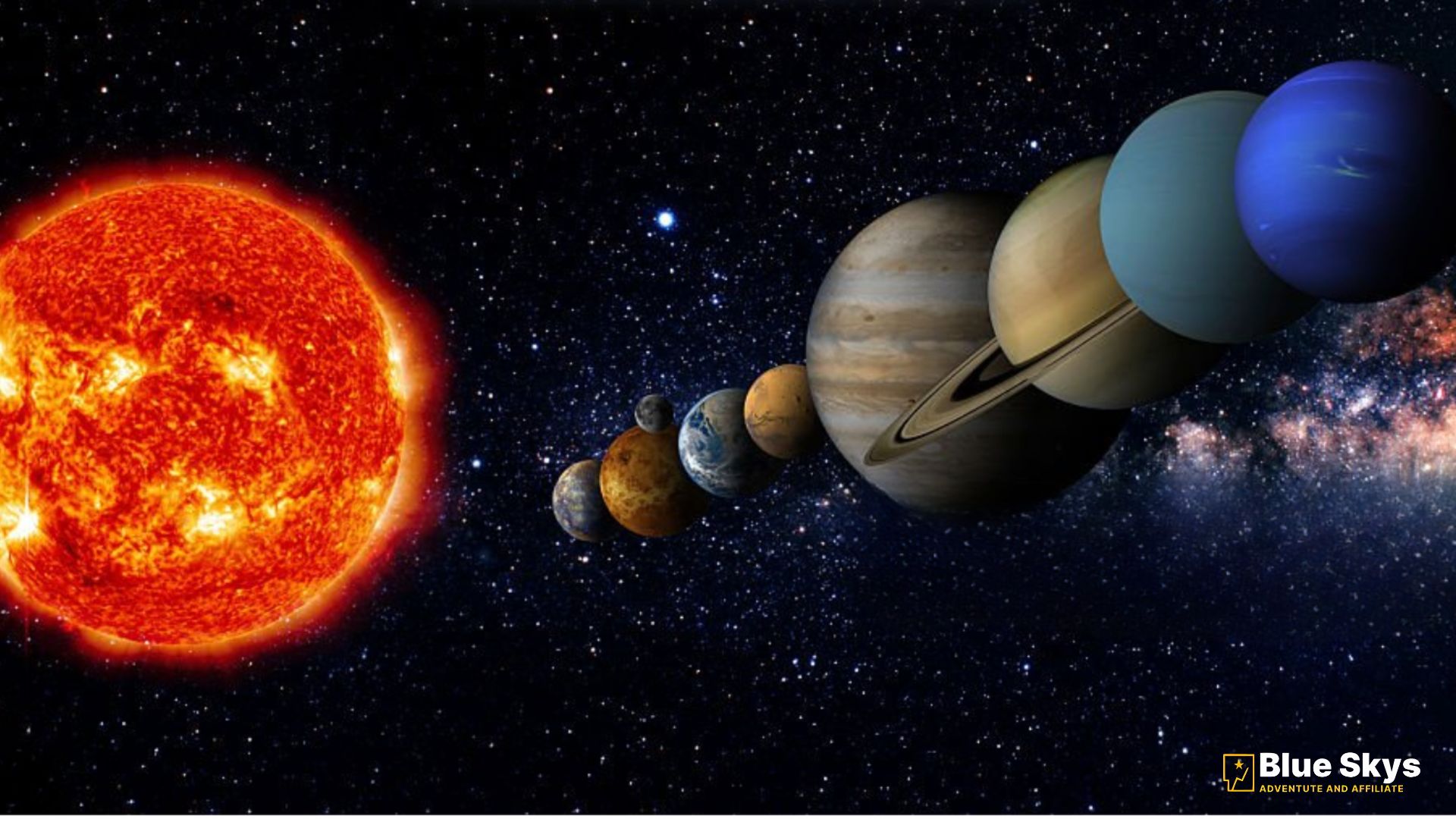

The term Ursa Major, translating from Latin as “The Greater Bear”, refers to one of the 88 official constellations recognized globally by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). It is the third-largest constellation in the sky and encompasses a vast region of stars beyond the famous seven.

In contrast, the Big Dipper is an asterism—a prominent nickname for the pattern that looks like a ladle, scoop, or wagon. By recognizing that the Dipper is merely the tail and hindquarters of the much larger Great Bear, observers gain a deeper appreciation for its true scale.

Following the Arc to Other Stars

The Dipper’s structure acts as a reference point for locating other constellations, not just the North Star. Astronomers use the famous mnemonic: “Arc to Arcturus.”

The arc is formed by the three stars of the Dipper’s handle (Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid). Following this graceful, sweeping curve away from the bowl naturally leads the eye to Arcturus, a bright red-orange giant that is the primary star of the constellation Boötes.

Mythology and Cultural Significance

The rich history surrounding Ursa Major offers a compelling look at how various human cultures have interpreted the cosmos.

The Classical Tale of Callisto and Zeus

The most pervasive Western narrative comes from Greek mythology. The story explains the constellation’s peculiar, long tail—unnatural for a biological bear. The myth tells of the nymph Callisto, who was transformed into a bear by Zeus to protect her from the jealous rage of Hera. Zeus then seized the bear by its short stubby tail and violently flung her high into the heavens, permanently stretching the tail into the long form seen in the stars today.

Legends of the New World

In the United States, the Big Dipper holds profound historical significance. During the era of slavery, the asterism was often referred to as “The Drinking Gourd.” Enslaved people relied on the Dipper’s Pointers to locate Polaris, which reliably directed them north toward freedom on the Underground Railroad.

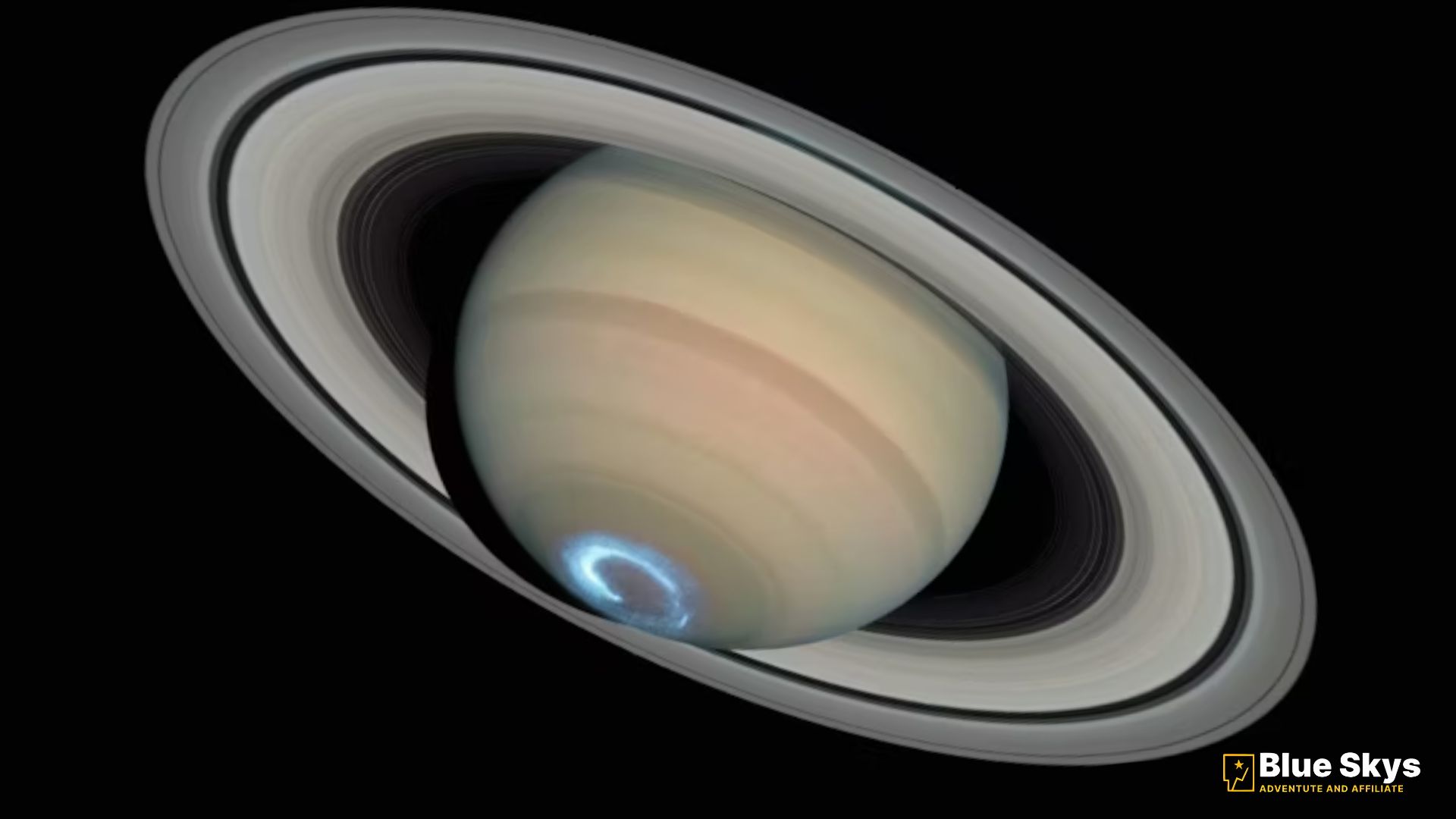

Deep-Sky Wonders: A Window to the Universe

Ursa Major looks away from the dense dust of the Milky Way, giving us a clear window into deep space. It contains some of the brightest galaxies visible from Earth.

Key Galactic Targets

- Bode’s Galaxy (M81): A magnificent, bright spiral galaxy.

- The Cigar Galaxy (M82): A “starburst” galaxy seen edge-on, physically interacting with M81.

- The Pinwheel Galaxy (M101): A large, beautiful face-on spiral galaxy located 21 million light-years away.

📸 Photographer’s Recipe: Capturing Bode’s Galaxy (M81)

Target: M81 & M82 (The Cigar Galaxy)

Difficulty: Beginner / Intermediate

You don’t need a Hubble Telescope to photograph these galaxies. Here is the starter recipe for a standard DSLR + Tripod:

- Lens: 200mm – 300mm telephoto lens

- Aperture: f/4 or f/5.6 (wide open)

- ISO: 1600 or 3200

- Shutter Speed: 1.5 to 2 seconds (without a tracker)

- The Secret: Take at least 100 photos (“lights”) and stack them using free software like DeepSkyStacker to reveal the spiral arms.

The Dipper’s Dynamic Future

The stars are not stationary. They are moving independently through space (Proper Motion). Scientifically, it is predicted that in approximately 100,000 years, the seven stars will have moved far enough apart that the Big Dipper will lose its ladle shape, appearing more like a “shoe.” This confirms that constellations are temporary snapshots in cosmic time.